5 min. read

Last updated Feb 9, 2026

Key takeaways

Afforestation, reforestation, and revegetation activities (ARR) fall under a single carbon removal project category, but each represents a distinct process with different environmental and social benefits.

Distinguishing afforestation and reforestation projects can be challenging as it requires an understanding of the site’s previous history, but doing so is essential to avoid inappropriate siting, stakeholder concerns, and questions about carbon integrity.

ARR is the most undersupplied nature-based carbon removal pathway.¹ As demand grows, it is critical for developers and buyers to properly classify these projects.

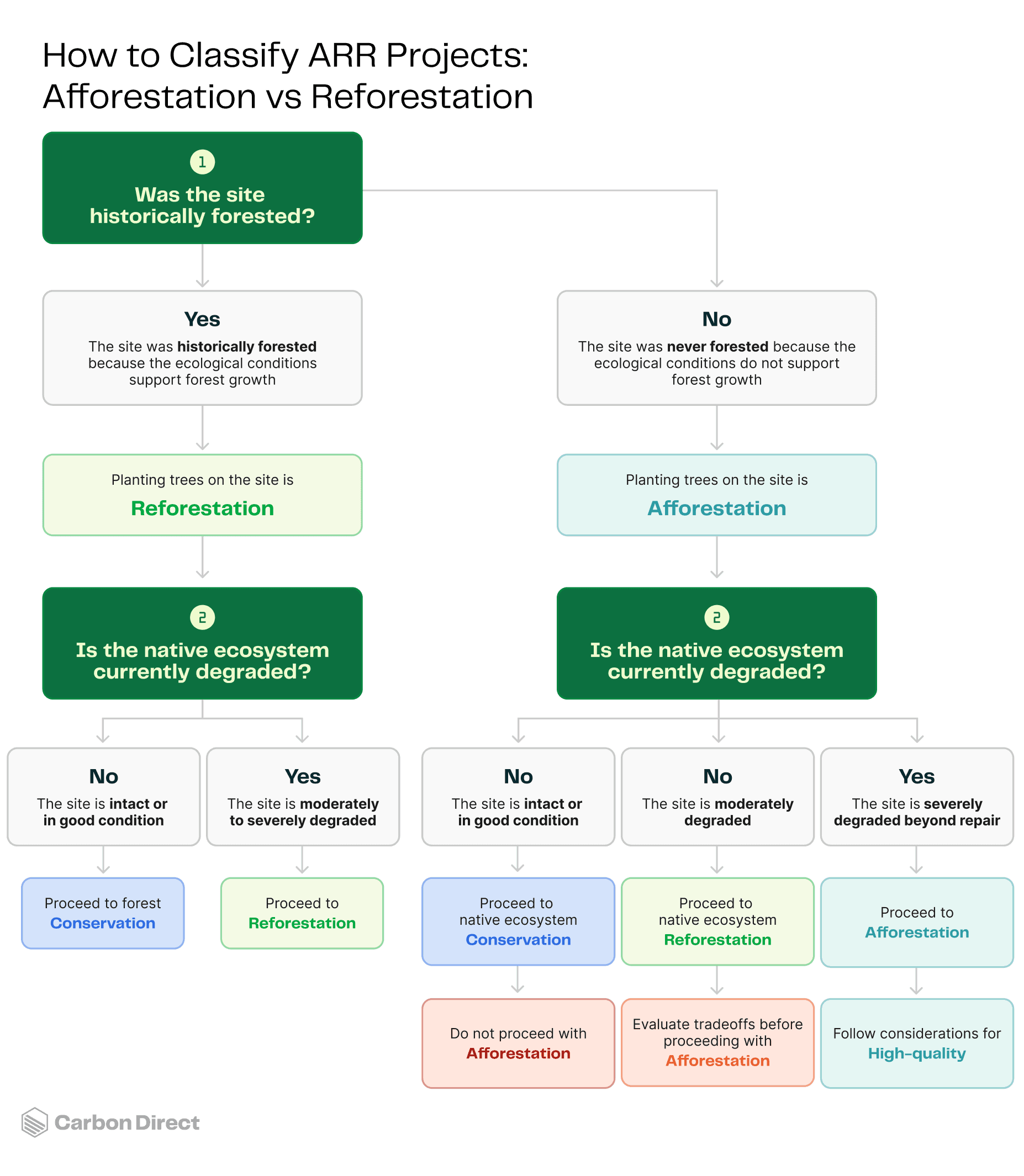

Our simple two-question framework clarifies whether a project is afforestation and whether it is sited appropriately. This approach helps developers avoid costly mistakes and supports high-quality implementation.

ARR carbon removal projects: A scalable climate solution

To meet the Paris Agreement’s climate goals, carbon dioxide removal must exceed 7 billion tonnes annually by 2050. Nature-based solutions (NbS) could deliver over one-third of the cost-effective climate mitigation needed by 2030, making them an essential climate action strategy.

Afforestation, reforestation, and revegetation (ARR) projects store carbon in areas that previously lacked forests or other vegetation or where clearing or degradation have impacted the existing vegetation; these approaches represent one of the most scalable NbS strategies available today. When properly implemented, ARR projects can deliver multiple environmental and social co-benefits beyond carbon storage. Best-in-class ARR projects strive to avoid monoculture, use native species when possible, improve soil health, restore degraded habitats, support biodiversity, and help build resilient communities.

Rising demand for carbon removal credits with stricter integrity standards has driven increased investment in ARR. Since 2018, funds have raised more than $5 billion with an explicit mandate to generate ARR credits.²

In the voluntary carbon market (VCM), high-quality ARR credits can command a price premium reflecting buyers’ expectation of stronger additionality, greater transparency, and the potential for multiple co-benefits.

The ARR project classification challenge

Although afforestation, reforestation, and revegetation are different activities, the terms are occasionally used interchangeably when they should not be. Here, we focus on the distinction between afforestation and reforestation, the two most common types of ARR projects. While both approaches involve establishing trees, they occur on sites with fundamentally different historical conditions (see below).

Project developers sometimes misclassify afforestation projects as reforestation. While neither approach is inherently superior, afforestation can be controversial and requires careful consideration to avoid specific harms. Accurate project classification indicates that the developer has adequately considered the implications of site selection and aligned the project with broader carbon integrity standards.

Afforestation vs. reforestation: What is the difference?

Understanding when an ARR project is afforestation versus reforestation starts with clear definitions.

Afforestation involves planting trees in areas where the ecological conditions have not historically supported forest growth (e.g., grasslands, wetlands). This means introducing forests to landscapes that were naturally treeless.

Reforestation involves replanting trees in areas where forests once existed but were lost or degraded. This means restoring forests to sites within their historical geographic range. Reforestation can take diverse forms, from single-species plantations aimed at production to multi-species native tree stands aimed at restoring forest function and its self-sustaining dynamics.

The distinction between afforestation and reforestation begins with determining whether the site historically supported forests under ecological conditions similar to those of today. In other words, the key question is whether forests naturally persisted at the site during periods comparable to the present, rather than whether forests existed there during distant geological eras as inferred from pollen records.

In some cases, afforestation can entail significant climatic, ecological, or social tradeoffs and is therefore not appropriate. However, afforestation may be desirable on severely degraded lands—areas that have experienced long-term declines in productivity, ecological integrity, or human-valued services. In such contexts, recovery of the original ecosystem may require significant human intervention or may no longer be feasible. This includes human-dominated landscapes where afforestation supports ecosystem services and social values, with relatively limited ecological trade-offs (for example, planting agroforestry systems on degraded land).

Examples of severe degradation include salinization, desertification, soil erosion, soil compaction, and encroachment by invasive species.

Why does the distinction matter?

The distinction between afforestation and reforestation is important for several reasons, with significant implications for project quality and ecological integrity.

Ecological considerations

Not all landscapes are suitable for forest growth. Even if trees can survive in areas where they do not naturally occur, establishing forests in these locations can create unintended negative consequences.

Natural grasslands and savannas are complex, often ancient ecosystems hosting unique biodiversity assemblages and provide critical ecological functions. Nevertheless, they are often targeted for afforestation. Attempting to convert these ecosystems by planting trees can cause significant ecological harm with far-reaching impacts.

For example, planted forests can displace native species and alter natural disturbance regimes (i.e., fire, seasonal flooding), resulting in the local extinction of grassland-dependent species, causing irreparable damage to key functions, such as hydrological regimes or biogeochemical cycling, and profoundly impacting deeply rooted local cultural values.

Climate change considerations

From the carbon cycling perspective, planting trees in previously unforested areas can actually lead to carbon loss. Native grasslands store significant amounts of carbon below ground in extensive root systems and soil organic matter, especially in high rainfall regions. Consequently, converting these grasslands to forest can lead to long-term reductions in carbon storage.

In addition, planting forests on previously unforested areas can reduce albedo, the fraction of sunlight that a surface reflects back into the atmosphere. Light-colored surfaces, such as grasslands, reflect more sunlight back to space and absorb less heat. Dark forest canopies, by contrast, absorb more sunlight and trap heat. When afforestation replaces light grasslands with dark forests, the additional heat absorbed can counteract the climate benefit of the carbon stored in the trees. This is especially true in high latitude regions (e.g., boreal and some temperate), and to a lesser extent, in some tropical grasslands and savannas.

Therefore, while sometimes appropriate, developers should only pursue afforestation when the benefits (e.g., climate mitigation and/or adaptation) clearly outweigh the potential harms (e.g., biodiversity loss, reduced albedo). Careful evaluation of all trade-offs is essential to ensure responsible and effective implementation.

A straightforward decision matrix for ARR projects

To help ARR project developers and buyers determine when their project is afforestation versus reforestation—and when afforestation is ecologically appropriate—we propose a straightforward two-question decision matrix. This framework aligns with existing ARR protocols and provides clarity before developers invest significant resources (Figure 1).

Question 1. Was the site historically forested?

YES—ecological conditions historically supported forest growth:

Planting trees constitutes reforestation

Reforestation is generally appropriate

NO—the site was not historically forested:

Planting trees constitutes afforestation

There is a risk of altering the native ecosystem

Proceed to Question 2 to determine whether afforestation is ecologically appropriate.

To determine whether a site historically supported forest growth, developers can draw on a variety of resources including local records, traditional ecological knowledge, peer-reviewed literature, and global ecoregion maps or models. Developers should cross-reference these resources for accuracy.

Question 2. Is the native ecosystem currently degraded?

The land is intact or in good condition:

Conservation and restoration approaches that maintain or recover the natural ecosystem are appropriate

Afforestation is not appropriate

The land was previously forested and is now moderately or severely degraded:

Reforestation is generally appropriate

The land was previously non-forested and is now moderately degraded:

Restoration of the original ecosystem is generally appropriate

The land was previously non-forested and is now severely degraded:

Afforestation is potentially appropriate if recovering the natural ecosystem is no longer feasible and the trade-offs are minimized

Important caveat: Areas that have been identified by relevant legal or national authorities as restoration priorities may be inappropriate for afforestation, despite severe degradation

Developers should consult local records and local experts to diagnose the land condition and its degree of degradation. Developers should cross-reference these sources carefully, as highly degraded sites that support critical biodiversity or ecosystem services may already appear on local or national restoration priority lists, and are therefore unsuitable for afforestation.

Five considerations for high-quality afforestation projects

Carbon Direct’s Criteria for High-Quality Carbon Dioxide Removal emphasizes that afforestation should only be pursued in ecologically appropriate areas with significant degradation. For developers whose projects have passed the framework above, the following guidance provides additional considerations to support high-quality implementation.

Avoid native grassland and savanna ecosystems

Even if trees can grow in these environments, replacing native grasslands can deplete biodiversity and soil organic carbon, and significantly alter hydrological, light, and fire regimes, while also impacting climate dynamics.

Exclude sites with existing biophysical challenges

In water-stressed areas, trees generally have higher evapotranspiration rates than other native vegetation, which can disrupt hydrological cycles and negatively impact ecosystems and downstream communities. In high-latitude or high-albedo areas, replacing existing vegetation with a dark forest canopy may reduce or negate carbon benefits. Developers should avoid afforestation in these contexts.

Forgo afforestation when biodiversity conservation is a top priority

Native species are adapted to their original ecosystems, and replacing these with forest cover typically does not support local biodiversity. Developers should use diverse, regionally appropriate species, avoid non-invasive or exotic species, and preserve any remnants of the original ecosystem.

Focus efforts on degraded areas with community support

Target degraded areas that do not currently provide key environmental and social services, where there is community support, and where less intensive strategies (e.g., fire management) are unlikely to succeed. Developers should avoid planting in areas where trees may compete with food production or livelihoods.

Engage local ecologists and monitor long-term ecosystem changes

Early detection and adaptive management are essential to address unintended consequences when transforming native ecosystems. Developers should document and transparently disclose any trade-offs resulting from ecosystem transformation.

The path forward for ARR carbon removal projects

As ARR projects continue to expand globally, afforestation will remain a valuable strategy in the carbon removal toolkit. However, to minimize harm, successful projects depend on accurate classification and appropriate site selection from the outset.

For ARR project developers, using this framework to correctly identify when their project qualifies as afforestation helps ensure that the project is appropriate, delivers the intended climate benefits, and builds stakeholder trust.

For carbon credit buyers, understanding the distinction between afforestation and reforestation supports stronger diligence and reduces risk when evaluating ARR projects.

Accurate classification and appropriate site selection help avoid unintended impacts and support projects in meeting high-quality standards for carbon integrity and long-term climate benefits.

How Carbon Direct supports ARR carbon removal projects

ARR carbon removal projects offer a powerful path to sustainable land use through ecosystem protection and restoration. Achieving this potential requires accurate classification, ecological rigor, and careful design that avoids unintended harm.

Carbon Direct empowers project developers and carbon credit buyers to navigate these complexities and invest confidently in high-quality NbS carbon initiatives.

Contact us to discuss your ARR project and ensure it meets high standards for environmental integrity and carbon impact.

¹ According to Carbon Direct analysis of major carbon registries, the ratio of ARR credit issuances to credit retirements is ~1.5 ARR.

² Based on Carbon Direct analysis of publicly announced capital flows.